Paying a Living Wage is Anti-Racist

For organizations and institutions that are on the long, and never-ending path towards anti-racism, there are a lot of fronts to work on. To increase equity, diversity, and inclusion, workplaces can and should consider everything from hiring to working conditions to benefits to meeting structures, and more.

Making workplaces safer and more welcoming for Black and POC workers through HR policies is a crucial part of anti-racism in the workplace. But it isn’t the whole piece. Money matters when we’re talking about racism and its effects. Paying workers a living wage is a crucial part of anti-racism in the workplace, especially for entry-level positions. This is true whether you are paying people on an hourly basis or with an annual salary.

Race, Class, and Wealth are Tied Together

Race and class are inextricably linked. Not only do we have a wage gap between white workers and workers of other races, we have a widening wage gap in the United States. According to Nonprofit Quarterly, median white household wealth is expected to rise whereas Black and Latinx household wealth is trending downwards such that by 2053 the median wealth of a Black family will be zero and by 2073, so will the median Latinx family wealth.

A 2017 report from Prosperity Now and Institute for Policy Studies indicates that white households are projected to own “86 and 68 times more wealth than Black and Latinx households, respectively.” Plus, Black and Latinx people are much more likely to be in a more precarious economic position as a result of COVID-19.

Legacies of redlining have boxed Black potential homeowners out of affordable housing starting in the 1930’s, preventing Black people from getting loans or other financial services that would have made it possible to generate wealth to pass resources from generation to generation.

This is to say nothing of the fact that basically the entire U.S. economy is built on the legacy of stolen labor and violent exploitation of enslaved people.

The problem extends beyond what an individual’s paycheck looks like. Without a fair wage, people aren’t able to build enough savings to avoid predatory payday loans in case of emergency, they aren’t able to help family members offset costs of higher education, pay for a mortgage to build equity and generational wealth.

This means that anti-racism at work has to address cold, hard cash.

Underpaying Workers Decreases Diversity and Talent Retention

Many arts, nonprofit, and cultural sector jobs under pay employees, especially for entry-level positions.

These employers tend to do this because they feel like they can’t afford to pay employees better out of fear for their bottom line, but also out of habit. There’s often a sense that you need to suffer through unpaid internships, bad paying jobs, and a few years of barely scraping by to show your dedication to your career choice. But when industries refuse to pay employees enough money to support their basic needs and allow them to save for the future, they privilege workers that come into those jobs with wealth and privilege, which often falls along racial lines.

People who can afford to work for very little money often come from inherited wealth. They might get family assistance to help them pay rent or cover some living expenses. Even someone who doesn't receive an allowance from family members might be able to scrape by on low wages because they know that they stand to inherit money or assets from family members down the line. These kinds of financial cushioning make it possible to survive even if the paycheck that someone takes home from a job is laughably low.

All of the institutions that pay very low wages, intentionally or not, end up being more accessible as workplaces to the people who come from generational wealth, which is most often white people.

When cultural institutions think about how to hire and retain Black and POC workers, paying a wage that doesn’t silently depend on inherited money is key.

An anti-racist hiring strategy isn’t just about checking for bias in the job listing, thinking about where you are posting your listing, and whether you are searching for skills, talents, and abilities versus experience or credentials. It’s about whether you are able to pay people appropriately for their labor.

Job applicants will just not apply to jobs that can't support them, which means that any potential pool of applicants for jobs that underpay staff will be less diverse and more white.

Even for people that do end up applying and getting hired for low-wage jobs, it’s hard to stay and grow in a career or a field that underpays you. Workers who aren’t able to make ends meet or live comfortably on the salary they are earning often have to take second jobs. Working multiple jobs at once leads to burnout, exhaustion, and resentment.

If someone is working one or more side-jobs in order to supplement the pay from a job in their preferred industry, they might find it hard to move up in that industry. In order to succeed in lots of industries, you need to be able to find time to cultivate mentors, make connections across the industry, and other time-consuming activities that are hard to manage if you have to rush to your night job or can’t afford to attend a networking event.

It doesn’t matter how many Black or POC people an organization or institution hires if that institution keeps hemorrhaging staff because nobody can live on the wages it pays without outside help or a second job.

But perhaps the most obvious reason that paying a living wage is anti-racist is that it is oppressive to not compensate people fairly for their labor. That’s true across racial lines, but it’s especially damaging for Black and POC people who have been historically exploited out of the real value of their labor in this country.

Finding a Living Wage

So, if you as an organization have decided that you want to ensure that you are paying workers appropriately, the first step is figuring out what a livable wage is.

If you pay workers at an hourly rate, $15 is the absolute minimum you should be considering. In 2012, workers started to agitate for a $15 per hour minimum wage. But because it’s been almost a decade since those workers first came together across industries to push for $15 per hour and costs of living have increased, $15 should be the floor, not an aspiration. Plus, it’s worth learning about how the minimum wage in the United States has disproportionately negatively affected Black workers.

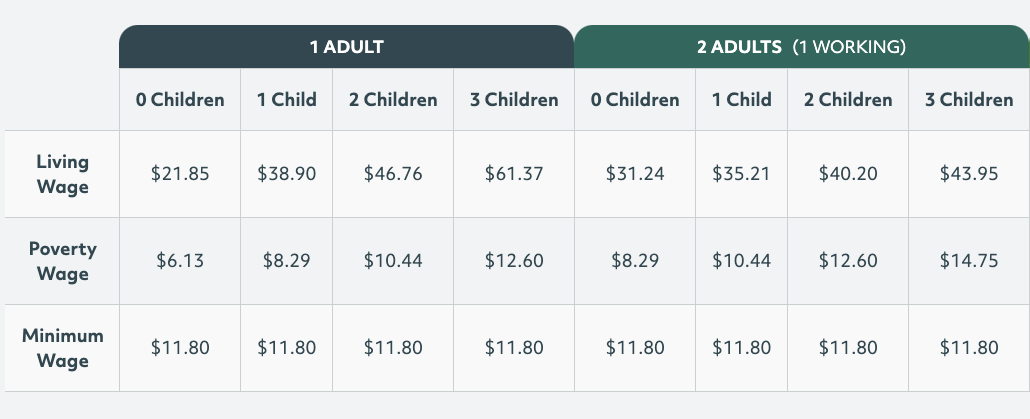

For both hourly and salaried workers, MIT has a living wage calculator. Using this calculator, you can plug in states and counties to see what a living wage looks like. The calculator considers expenses like food, childcare, medical expenses, housing, transportation, and taxes. For example, in Queens County in New York City where I live, the living wage is $17.99 an hour for a single adult with no children. The calculator shows the different living wages for single adults, multi-adult households, and households with zero, one, two, or three children.

Tools like the MIT living wage calculator can be useful, but you can also go with your gut. If your organization is based in a city like New York, you don’t need a web tool to tell you that $30,000 isn’t enough money to live on.

We Need Change at All Levels

To make our institutions better, we need more Black, POC, Indigenous leadership at the helm. We need to change institutions by changing who is in charge of them but we also need to focus on efforts to improve working conditions and compensation for the broader working class. Not everyone wants to or will ever be in the c-suite or at the upper echelons of an institution, and they shouldn’t have to be in order to have a safe and supportive workplace.

In order to create institutions that are welcoming to people at all levels and in all departments, we need to pay people enough so that they can find safe, comfortable housing, feed themselves and their families, save for the future and for emergencies, while still being able to afford a quality of life that is more than just scraping by.

So much of the work of anti-racism has to do with money, with working against the legacies of exploited, stolen labor of Black people. It has to do with talking more openly about money, which is why we think that not only is paying a living wage an important part of anti-racist work, pay transparency is, too.

About Nina Berman

Nina Berman is an arts industry worker and ceramicist based in New York City, currently working as Associate Director, Communications and Content at Fractured Atlas. She holds an MA in English from Loyola University Chicago. At Fractured Atlas, she shares tips and strategies for navigating the art world, interviews artists, and writes about creating a more equitable arts ecosystem. Before joining Fractured Atlas, she covered the book publishing industry for an audience of publishers at NetGalley. When she's not writing, she's making ceramics at Centerpoint Ceramics in Brooklyn.