What I’ve Learned on My Nonbattical

Back in February, I announced that I’d be temporarily stepping aside from ordinary CEO duties at Fractured Atlas to work on creating a new impact investing fund. Dubbed The Exponential Creativity Fund, this new effort would invest in entrepreneurs and innovators at the intersection of technology and human creativity. For the first couple of months I was pretty good at posting regular updates and meditations, but I confess I have been remiss of late. Time to get caught up!

So without further ado, here’s what I’ve learned on my nonbattical:

Our investment thesis is coherent and persuasive.

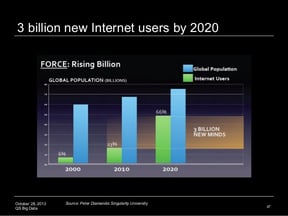

Investment decisions should be guided by a specific worldview, which in turn is built on the observation of social and/or economic trends. Through 20 years of experience as a technology company that serves artists, we have some observations and theories about the role and continuing development of technology related to human creativity. During the past six months, we’ve rigorously interrogated these ideas. At this point, I am confident that the underlying trends we’ve observed are real, meaningful, and enduring, but not yet widely recognized. All things being equal, this is the foundation of a successful investment strategy.

Fractured Atlas is an attractive investor to companies in our focus areas.

We have received this feedback consistently from both (i) artist founders without deep business backgrounds and (ii) experienced entrepreneurs engaging the arts community for the first time. This was vital to confirm. The best startups and founders (with some problematic exceptions) generally have no trouble raising money and can take their pick of investors. We will never be competitive based on the depth of our pockets, so we’d better have something compelling to offer in addition to a check.

There are ample opportunities to achieve a positive mission impact from our investments.

There are lots of great startups doing important work in the areas we care about. Some of them are explicitly mission-driven while others are doing good as a byproduct of the pursuit of profits. Either is fine with me. But in both cases, measuring the non-financial impact is hard. This is especially true as compared to other social entrepreneurship efforts. As we set out to raise our fund, this limits our appeal to philanthropically-minded investors.

Raising $10 million is hard.

I’ve had a fair amount of success raising money from philanthropic sources over the years, but raising money from investors is a whole new challenge. In some ways, raising a $10 million venture capital fund is actually harder than raising a $200 million fund, because there are many traditional fund investors that can’t participate at such a “small” scale. This was probably to be expected, but it suggests we would face a long runway to closing a traditional closed-end fund at this level.

Track record matters a lot to investors.

While “past performance is not indicative of future returns” it is nonetheless the primary data point that investors use in fund selection. This is true despite data showing that first-time funds actually outperform the veterans. Attracting significant capital will likely require that we demonstrate some record of success as investors in this space.

We can achieve highly competitive investment returns from a well-designed and well-executed strategy.

Research and analysis both support this hypothesis. To whatever extent you can model a portfolio on paper and spreadsheets, I’ve done it, right down to the Monte Carlo simulations. Clearly playing with spreadsheets is very different from deploying actual capital, but in general the numbers look good.

Some otherwise attractive investment opportunities are poor fits for the venture capital model.

These mainly include businesses that are likely to achieve both mission impact and strong financial returns but not at the “unicorn” scale that traditional venture capital models require. Fortunately, there are lots of other ways to finance these businesses, from debt instruments to revenue-sharing agreements. Any strategy we pursue has to be able to deploy tools like these when warranted.

Where does all of this lead us? Hopefully to a place that’s pretty exciting, where we’ll be able to support some innovative founders doing important work and make some money for our investors while we’re at it. But it’s not yet time for the big reveal, so you’ll need to stay tuned for another update in the near future. In the meantime, don’t be shy about reaching out to me if you’d like to connect about this work. The best way to find me is at [my_firstname].[my_lastname]@fracturedatlas.org.

About Adam Huttler

Adam Huttler is the founder and Managing General Partner of Exponential Creativity Ventures. As a six-time founder, his career’s through-line has been about helping mission-driven companies use technology to drive innovative revenue strategies. Adam is best known as the founder of Fractured Atlas, a social enterprise SaaS platform that helps artists and creative businesses thrive.