We’re Sick of Zoom: Why and What to Do About It

Soon enough, we’ll have to stop saying “these past few months” or “since March” when we want to refer to ways that the COVID pandemic has upended our lives because it’s about to be March again and we will soon be one full year into this.

Now that we’re approaching the year-mark of COVID in the United States, it’s worth it to pull back and think about how we’ve used the remote work tools at our disposal and how we should use them going forward.

In Spring 2020, we put out as much information as possible about how to transition to virtual workplaces, which tools to use, how to manage, how to avoid remote toxic workplaces, and even laid out some of the challenges of working remotely. We were able to because we had done it already.

Fractured Atlas had already gone fully remote in 2019 and for us as an organization it was freeing. Our staff could live wherever they wanted and our hiring pool expanded beyond commuting distance to our midtown New York office. Tools like Zoom have helped us build a fully-distributed workplace. But now, we’re reflecting on the tools we use to work remotely.

Because, honestly, we're tired of them.

Why Are We Tired of Zoom?

In March 2020, there were 11.2 million downloads of Zoom.

When people started using Zoom in March, we were running on adrenaline and experiencing new heights of both anxiety and boredom. Zoom felt novel for many users, both professionally and personally. But now, it’s safe to say the shine has worn off as we’ve been in the long-haul.

At first, Zoom and other tools seemed like temporary aberrations to our daily lives which we would promptly return to after maybe a few weeks of staying in. But as the weeks and months have rolled on, video conferencing is still how many office meetings are happening and even how many of us have celebrated holidays with our family and friends. What seemed like a temporary stop-gap is now the norm.

Zoom isn’t just a tool that we’re using for work, it’s how many of us are staying in touch with family and friends. We’re not able to close the computer and be with our community at the end of the workday the same way we used to. A sad truth of my past year is that I’ve used the same interface to discuss the editorial calendar for this blog that I’ve used to celebrate Passover with my family.

The same place in your home, the same lighting setup, and the same gallery of faces that you see for work or school is the same that you see for fun or for rejuvenation. This sameness collapses the boundary between work and fun, making it all more exhausting.

Video conferencing, whatever platform you use, takes more brainpower than physical gatherings. Social cues are harder to read and to perform. You have to make more of an effort to demonstrate that you are engaged in the conversation, signaling to your colleagues that you are listening and absorbing information. You need to remember to not only be interested but look interested in a way that translates to the little gallery of faces. This is to say nothing of the extra mental work it takes to deal with spotty internet coverage, screen freezes, and accidentally talking over one another. In many ways, it’s harder to work together on Zoom than it is to work together in person.

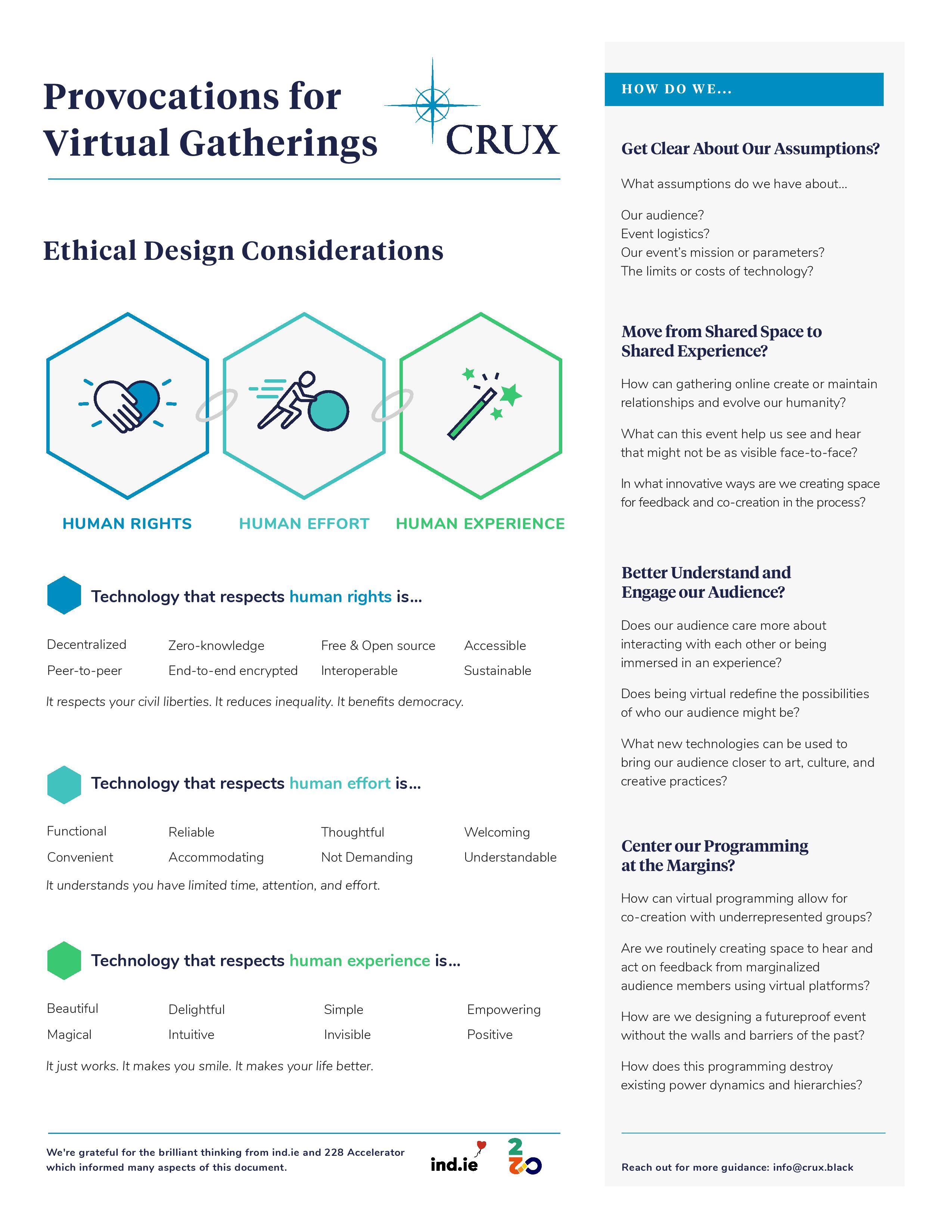

A larger concern is that Zoom, like many apps, is not actually designed with human wellbeing in mind. CRUX, a studio at the intersection of Black storytelling and immersive technology co-founded by our co-CEO Lauren Ruffin, suggests that ethical technology design should have a few key components that Zoom doesn’t currently have. Technology should respect human rights. It should be decentralized, free and open-source, accessible, end-to-end encrypted, and sustainable. It should respect your civil liberties. Technology should respect human effort. It should be built to understand that we all have limited time, attention, and effort.

And, importantly, it should value human experience. Technology should work. It should make you smile, it should make your life better. The problem with Zoom is that it isn’t any of these things. If a platform isn’t built with ethical design considerations in mind, we’ll always find ourselves chafing against it.

But until we have a tech utopia, we have to make do with what we’ve got. So… how exactly do we do that?

Bring Intentionality to Zoom and Video Conferencing

A huge issue with the way that workplaces use Zoom and other remote working tools is that they were adopted in an incredibly hurried way over the course of a few weeks. When we did a mass adoption of Zoom and remote work, it wasn’t done with intention. We now have to retrofit that intentionality back onto the way we work remotely.

First, you need to think about which meetings really need to happen. Maybe you and your team have a daily standup call. First, ask yourself and your colleagues if that meeting is necessary. Do you get social or professional value from it? Or do you only have some meetings because you’ve always had them? We’ve seen plenty of orgs just replicate the same meeting schedule they held in offices out of habit. But we encourage all workplaces to take a long, hard look at which meetings you need to have on the schedule and ask yourselves honestly what purpose they serve. If there’s no reason other than tradition to keep some standing meetings, nix them from the calendar! If you’re just scheduling meetings to make sure that people are on the clock, you have much bigger problems about management and trust to deal with before you get to your scheduling.

For meetings that you’ve determined are important, do they need to happen on Zoom? Could you accomplish the same goals if you used Slack or email instead of video conferencing? If you need to have the kind of meeting where everyone is working on the same thing at once, what if you just pulled up a Google Doc or Mural and everyone worked together that way? If you need to have a brainstorming session, what if you did it by phone to simulate a Sorkin-style walk and talk?

If you do need to talk with one another at the same time, you might also consider if you need to turn the video on. In the past, we’ve suggested norming video on for remote meetings. But now, we think that it might be good to normalize having video off if participants would prefer. You can still work together even if you can’t see each other’s faces.

Turning off video removes the added burden of making sure that your eye contact is in the right place or worrying that your partner might saunter into the frame fresh out of the shower. Turning off video functionality can also be an equalizer. If everyone is on video, certain markers of class and privilege are present in a way they wouldn’t be if a call was audio-only or if the meeting was taking place in an office or coffee shop. You can see who has good natural lighting, enough space in their home for a full desk or office setup, who has nice furniture or art in the background. You can also see if someone is sharing a workspace with a family member or roommate. It can make people feel uncomfortable or ashamed if they have to put their home life on display as their “office.”

It’s entirely possible to use only audio conferencing functionality. I’ve used Zoom and other video conferencing tools at a previous remote job. We just never turned the video on. It made it surprising to see people’s faces in person when we met for annual all-hands meetings, but we still managed to get to know one another, do our jobs, and collaborate with one another.

And, if you ever really just need a change of pace, you can explore meeting on other platforms to see if exploring something new helps ease some of the issues of video conferencing and virtual meeting.

Design Humane Workplaces

The problem with Zoom is really much bigger than an individual app. It’s even bigger than the challenges we’ve faced with a mass move to virtual work. The underlying problem is that workplaces aren’t designed thoughtfully. Problems are solved as they arise in the most expedient way possible and then that expedient solution somehow becomes the permanent solution.

Changes we made to our working lives in March 2020 were made under duress, anxiety, and uncertainty. We also thought that they were much more temporary changes than they have turned out to be. Some organizations are never going back to their offices. Others won’t be returning for a long time. Some will opt to offer permanent remote options. Whenever we return to some semblance of normal, our working lives will be forever shifted. The systems we set up while in crisis mode should not be the systems we use for the long term.

We urge organizations to think expansively, humanely, and creatively about how you are designing your workplaces, even when those workplaces are people’s homes. And, if you want to talk about how to design your workplace, drop us a line.

About Nina Berman

Nina Berman is an arts industry worker and ceramicist based in New York City, currently working as Associate Director, Communications and Content at Fractured Atlas. She holds an MA in English from Loyola University Chicago. At Fractured Atlas, she shares tips and strategies for navigating the art world, interviews artists, and writes about creating a more equitable arts ecosystem. Before joining Fractured Atlas, she covered the book publishing industry for an audience of publishers at NetGalley. When she's not writing, she's making ceramics at Centerpoint Ceramics in Brooklyn.

-866351.jpg)