Language as an Essential Tool for Envisioning Change

Language in "These Unprecedented Times”

The protests ignited by George Floyd’s murder are still going strong as the public demands changes to the systems of the past that have perpetuated injustices. Artists have played a large role in this movement. This isn’t new. Artists have always been integral to social justice movements. From Emory Douglas’ drawings that are now widely associated with the Black Panther Party to the three queer Chinese American performance artists (Kitty Tsui, Merle Woo, and Canyon Sam) that started the Unbound Feet Collective moving Asian American feminism forward. Artists can affect great change.

Artists have shown up in various ways to support the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. Some have created beautiful, powerful signages that were shared widely across social media platforms to amplify the message that Black Lives Matter. Other visual artists, galleries, and collectives have donated portions of the sales of work towards various causes. For example, Ortega y Gasset Projects auctioned work with 100% of proceeds going to The Black School. Even while artists themselves faced great challenges due to the pandemic, their generosity has been astounding to witness.

Just as the United States continues its long overdue reckoning with race and oppression, Fractured Atlas’s anti-racism and anti-oppression work is ongoing as well. As the organization tackles this work, I reflect on what this means to me as a staff member and one part of the arts ecosystem.

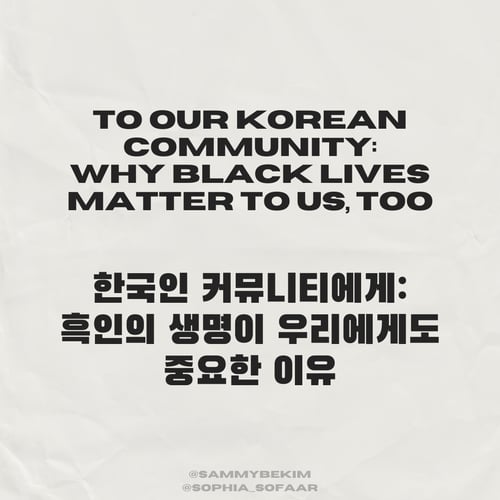

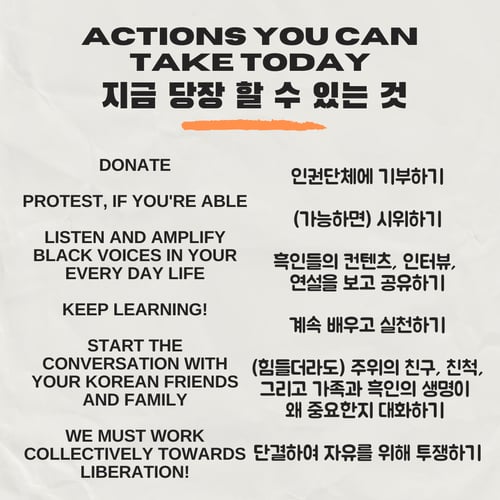

One way others in my community and I have interacted with the Black Lives Matter movement is through language justice. As a bilingual person, the first way in which I reacted to the movement was to start translating documents and infographics for my monolingual Korean community.

As Fractured Atlas and other arts groups and collectives continue on this journey to make all of our programs and services accessible, I am reflecting how language is often left out and what we can do to address this.

Is Language Political?

Language is essential. We use it to communicate with the world at large. Because it’s an innate part of us, it’s easy to forget that it is a tool with which we engage with the world. Because we use language to access different parts of the external environment we live in, it is inextricably linked to systems of oppression that we are all affected by. Language is connected to the transnational histories of colonization; dangerous discrimination exacerbated by racist, ableist, sexist systems, and more. Because of this, language is political.

Systems of oppression affect us differently depending on who we are. Lack of language access works similarly. There are two ways in which inequality in language access can be identified. First is the lack of language access due to the decimation of your language because of imperialism and colonialism, which have enacted intentional cultural genocide. Think of the forced attendance of Native Americans from the 1800s to 1900s to boarding schools where loss of language was just one part of a series of policies that resulted in culture cleansing.

The second lack of language access is on a more local scale when there is an actual physical barrier to you being able to understand the dominant language in a particular situation. As an example, without an English language interpreter, a Spanish monolingual speaker might be unable to voice their opinion in an English language dominant situation. Power dynamics in language equity exist, and need to be addressed to make sure every individual can express themselves how they want.

One organization working to address the imbalance in power of language access is Wikitongues, whose work is dedicated to language preservation in the midst of a cultural renaissance of language diversity. The organization is creating frameworks for language preservation, revitalization, and sustainability that are rooted in local communities. With many languages across the world headed towards extinction, Wikitongues maintains a digital library of languages from all over the world to ensure they are not forgotten.

Daniel Bogre Udell, Wikitongues’s executive director, spoke with me about how Wikitongues’s work is tied to the great long history of language erasure linked with painful traumas of imperialism and colonialism. An example he gave is how Yiddish is no longer being widely spoken across the European continent due to the persecution of Jews during the Holocaust. Another example that is tied to my history is the purposeful erasure of the Korean language during the Japanese occupation. There are countless examples of language being used as a tool for cultural suppression.

As a result, the work of language revitalization is inherently tied to movements of decolonization, racial justice, and social justice. Udell gave an example of how it’s really not possible to talk about the Dakota pipeline and the activism around it without also talking about the persecution of the Lakota language. The injustices that exist in the world cannot be addressed without language. Udell shared that, “Language revitalization, in my mind, is a necessary reparation and necessary for any sort of true restorative justice.” Language revitalization and preservation set the stage for language justice practices.

The Power of Language Justice and Its Role in the Arts

As artists, it is critical to be able to express your full self or at least have the ability to select which parts of you to express. Artists may access many different modes of expression and language is included in them. From poets to performance artists to literary translators, whether language is spoken, written, visualized, it is all key to empowered self-expression. As artists create in this time it is important to remember that artists are connected to the greater world, whether it is to the viewer of your work or a patron supporting you financially. In this way, the principles of language justice should be part of an artist and/or an arts organization’s work to fully acknowledge the intersectional world that art exists and participates in.

Jen Hofer of Antena Aire, a language justice and language experimentation collective that incorporates cross-language practice and the spaces between languages into a range of artistic and literary endeavors, explains language justice slightly differently. They define it as “the idea that every person present has the right to bring their full self into the room and to participate with their whole self, in their language.” Language justice proposes a world where everyone’s expression is valued, and where the language rights of all people are respected.

As well as co-founding Antena Aire, Jen is an artist: a poet, translator, and bookmaker practices that are inherently linked to their work in language justice. Jen described that from the beginnings of Antena Aire (and its sister collectives Antena Los Ángeles and Antena Houston), in conjunction with their collaborator JD Pluecker, they realized that being artists whose primary material is language is not separate from language justice work. Building and organizing inform how they thought about art-making and helped them develop experimental approaches.

The power of language in this is key for José Eduardo Sánchez, an artist and member of Antena Houston, who recounts the transformative experience of participating in a social justice interpreting workshop as informing their organizing work with immigrant Latinx communities and social practice. There is a bi-directional intertwining of language justice and artmaking. Jen believes the power of art in movement building is to “help us see and listen and think differently and undo, an act of Audre Lordean dismantling of the everyday structures that we take for granted, and which are oppressive structures.”

Especially for artists engaged in work driven by social practice frameworks or who are creating work at the intersection of social justice movements, it is essential to think critically about how language plays in the work. Jen notes how language justice is more and more a space for healing, both for people from different communities who share common cause and for language workers who have experienced language trauma or other cultural violence as part of their own personal or family history. As creators who are trying to build a better world, utilizing language justice frameworks to make work can create better and more equitable spaces for engagement. When you engage in language justice work and practices, you create moments for true coalition-building between artists, community, and beyond.

It is also important to understand that this very important way of expressing yourself is not available to everyone. You can be a monolingual speaker living in a multilingual space or someone who communicates with sign language but lives in an able-bodied world. Knowing this, what can you do proactively in order to take language justice into consideration? How can you create an artistic practice that acknowledges and works to resolve power dynamics rooted in language inequity?

Strategic Questions for Integrating Language Justice Frameworks to Your Work as an Artist and Arts Organization

Language justice works to create spaces where no one language is more dominant than another language, and where the aim is for everyone to be able to freely express themselves with their language(s). It takes great intentionality to create these multilingual spaces. If you are an artist and/or arts organization looking to adopt language justice frameworks into your practice, I recommend starting with Antena Los Ángeles’s comprehensive checklist for building bilingual and multilingual spaces that is available on the resources page of their website.

The checklist provides detailed tasks from the event planning stage to after the event. Jen and José Eduardo provided some guiding questions and principles to apply in addition to implementing the checklist. One thing to note is that these are not unique to language justice necessarily but are built on from the organizing work that Black feminists and disability justice communities have done.

How can we slow down and work in slow time?

Jen shared the idea that “language justice time is slow time.” This involves putting care and attention into the various facets of the work. For me, this means artists and organizers need to make sure the success of a program isn’t about filling in all of the seats. Instead, anti-capitalist ways need to be integrated to make sure everyone is included so that seats are filled but more importantly, people can understand and express themselves fully with all the tools they need.

How are we holding the space?

Once you are moving slow, you will inevitably ask yourself the general question of how do you accommodate everyone and make sure they have a platform? Each person carries, processes, and expresses language in different ways. José Eduardo noted that many people come into spaces carrying a lot of shame, guilt, and discomfort about their ability to speak a language. If someone does not speak the dominant language, and even if they do, there can be a lot of stigma around speaking non-dominant languages. Understanding that the individual may carry trauma is important to keep in mind as spaces are created for the collective.

Additionally, in order to make sure the space is accessible to these nuances, the question to ask is “Whose voices do we want to center?” Naturally accompanying this question is then also the question of “How do we restructure spaces so that these voices are centered?”

What am I willing to give up because of my belief in social justice?

To ensure that spaces include everyone and are built on liberation is continuous work, as Jen points out, “Language justice is a process, it’s something we’re constantly engaged in.” One important question to ask in this continuous struggle for liberation is “what exactly are those in power willing to give up for justice?” Many organizations (in response to the Black Lives Matter movement) have quickly published diversity and inclusion pieces with a vague promise of change. José Eduardo’s question of how can we redistribute financial resources truly so that power dynamics are acknowledged is one way in which organizations and companies can keep to their promises.

Organizations can invest in creating spaces rooted in justice by really putting in the hard work, whether that is reconsidering budgets and redistributing resources to areas like language interpretation and access or creating true collaborative paths for partnership with the local community.

“Language as a Cosmovision”

Because language is essential, language justice is vital to the arts no matter what role you have in the arts ecosystem. The work is ongoing and ever-transforming to make spaces equitable so that artists can continue to create work and for arts organizations to create better community spaces. As José Eduardo beautifully put it, the dream can be for “language [to exist] as a cosmovision, not just a way of communicating with each other but as a way to experience and to live in it.” This is just the start to make this come true.

Anti-racism and anti-oppression work needs to be part of our daily lives. To help support that journey, please check out Fractured Atlas’s list of anti-racism resources for the arts and nonprofits.

About Sophia Park

Sophia Park (she/her) is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn, NY and Gumi, South Korea. She received her B.A. in Neuroscience from Oberlin College and M.A. in Curatorial Practice from the School of Visual Arts. Recently, she worked as a curator for the 15th Gwangju Biennale. Formerly, she worked as the Director of External Relations at Fractured Atlas, a national nonprofit arts service organization and taught entrepreneurship and the arts at New York University. She is part of slow cook, a curatorial collaboration with Caroline Taylor Shehan where they make programs and books, and is a co-founder of Jip Gallery (2018 - 2022). You can probably find her running some silly distance, trying to get back into tennis, or dancing somewhere.