ART/WORK Showcases a Precedent for Government-Funded Artist Support

As the art world considers the different ways that artists can be supported now and into the future, it can also be helpful to look to the past for successful models.

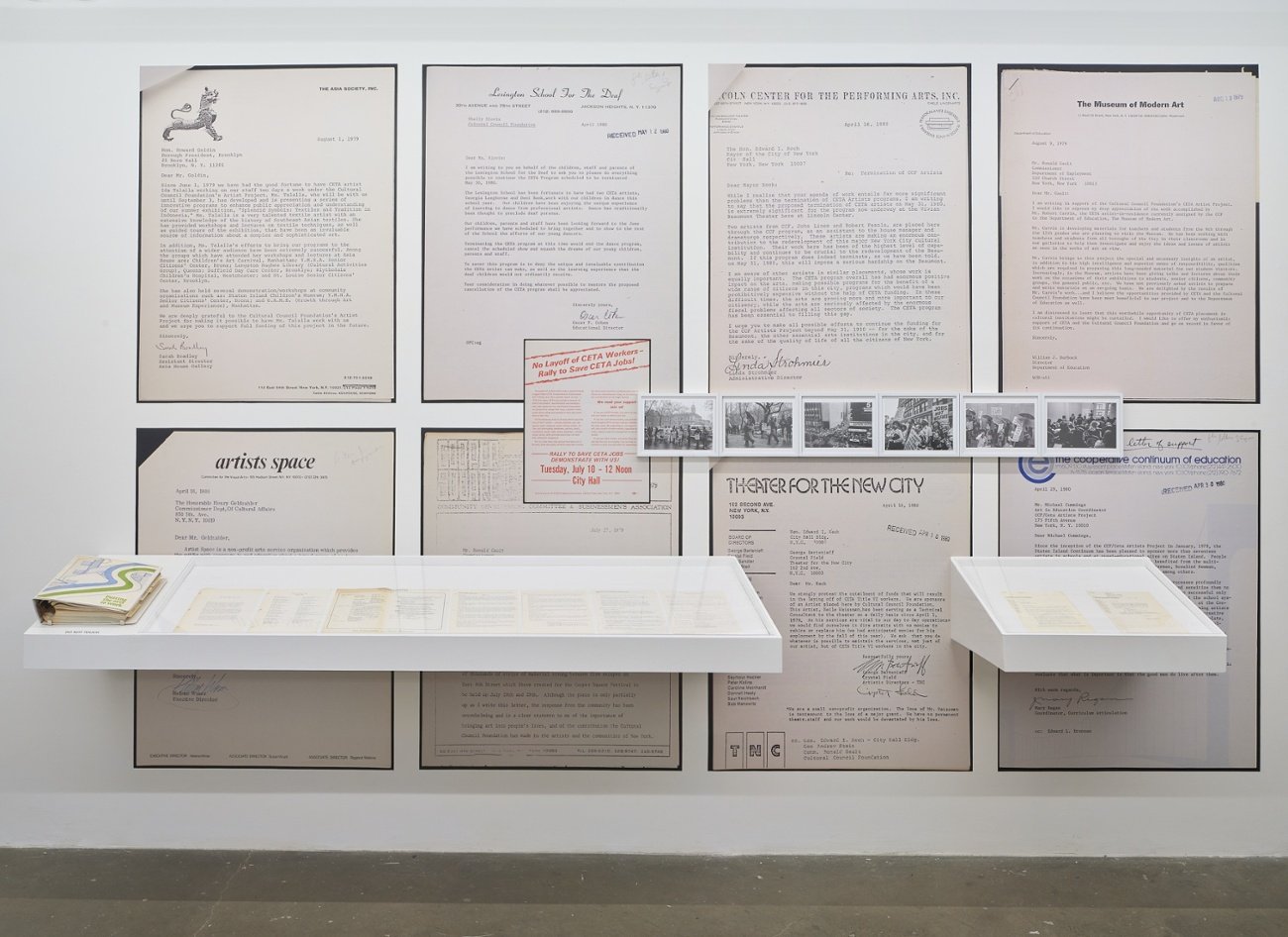

Artists Alliance and City Lore’s co-curated exhibition ART/WORK: How the Government-Funded CETA Jobs Program Put Artists to Work not only provides historical context for how artists can be supported, but also suggests an answer for the future to make arts support sustainable. The exhibition provides information on the federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) program, which operated between 1973 and 1981. The CETA program employed over 10,000 artists and cultural practitioners across the United States and 600 people in New York City alone. Artist support on this scale had not existed since the Work Progress Administration (WPA) program. We spoke to the co-curators of ART/WORK, Jodi Waynberg and Molly Garfinkel.

Jodi Waynberg is the Executive Director of Artists Alliance. She inherited the organization from a group of founding artists who built Artists Alliance as an advocacy organization. Now, Artists Alliance is focused on providing meaningful resources to emerging creative voices within the contemporary art field through exhibitions, direct payments to relieve economic burdens, free studio space, and commissions with community collaborators. Their programming sites include Cuchifritos Gallery, which was founded and is based inside Essex Market in the Lower East Side (LES) neighborhood of New York City.

Molly Garfinkel is a Co-Director at City Lore, a cultural conservation and cultural advocacy and education nonprofit. They have been in the LES since they were founded in 1985. The organization’s primary work is to document, advocate, and present living traditions in New York City. In addition to being a Co-Director of City Lore, Garfinkel serves as the Director of the Place Matters program, which is a public history-oriented community advocacy program. City Lore opened a gallery in 2014 to create a public space that people can access.

Jodi Waynberg. Image courtesy of Jodi Waynberg.

Jodi Waynberg. Image courtesy of Jodi Waynberg.

Molly Garfinkel. Image courtesy of Molly Garfinkel.

ART/WORK shows how artists play a critical role in larger society and the benefits that can come when artists are supported. Recently launched programs like Creatives Rebuild New York demonstrate that we are considering new ways of support for artists making exhibitions such as ART/WORK even more critical. The lines between art and labor are continuously negotiated especially in the capitalist-dominant society that we exist in. We talked with Jodi Waynberg and Molly Garfinkel about the importance of programs like CETA in reimagining how artists fit into the greater economy and what artist support can actually look like.

Before we get into CETA and to set the scene, I’m curious about how you balance working locally in the LES while serving a diverse population from all over the world?

Molly Garfinkel (MG): We are located in the LES, but we really work across the five boroughs. We document, present, and advocate for New York City’s grassroots cultures to ensure their living legacy in stories and histories, places and traditions. We work in four cultural domains: urban folklore and history; place advocacy and preservation; arts education; and grassroots poetry traditions. In each, we seek to further cultural equity and envision a better world with projects as dynamic and diverse as New York City itself. The backbone of the place advocacy program, Place Matters, is the Census of Places that Matter. It is an idea that was launched in 1996 as a collaboration between the Municipal Art Society and City Lore, and it was meant to offer new perspectives on how to value place and multiple narratives around place and history, largely from a grassroots or community perspective. The Place Matters project was founded to help identify, interpret, celebrate, and protect community landmarks, community anchors, and fragile sites that are critical to community cohesion and identity. So we wanted to provide a forum and an actual online presence for collecting this information and also again, to take ourselves out of the center to solicit this from the public to say that we're not the experts.

City Lore operates with a model of what we call shared authority. We don’t consider ourselves to be experts. We collaborate with communities and individuals to ask them to share their expertise with us, so that together we can help enhance the public record about what places matter and why. Maintaining local identity and valuing local perspectives and local needs is really at the center of a lot of what we do; we try to work from the grassroots up. We know the culture and social networks, and channels for community empowerment already exist, we just try to find ways to help to amplify them.

Jodi Waynberg (JW): For Artists Alliance, we are physically based in the Lower East Side (LES). And frankly, what we've looked at as a team over the last 10 years – though I would argue that the organization has been asking itself this question for its full lifespan – is what is the value and privilege of occupying and holding leases to spaces in the LES, which is increasingly inaccessible, particularly for the creative community?

When we were a part of the redevelopment project that ultimately resulted in the move of the former Essex Market into its new facility in Essex Crossing, we went through several years of stakeholder conversations and heartfelt, honest discussions internally as a team to really understand what it [signaled] for us to be a part of this redevelopment. What value can we offer to this community if we choose to move the gallery with the rest of the market and maintain our place in that community? And what do we have to change about our practices in order to move into this development and still hold the values and intentions of the organization? And so in the process of doing that, we thought very deeply about what it really meant to be a Lower East Side-based organization.

We continually work to understand what the community needs and what we can offer. Where can we offer a collaborative solution? And then, how can we ensure that the spaces we already have access to don't feel alienating or isolating? That's been a lot of our conversations, particularly about the redevelopment in Essex Crossing. We even considered the aesthetic communication of the building itself, and we talked about how to deal with the notion of thresholds: how do we address the idea of entering a space, coming into a space, recognizing whether or not you're welcome in a space? Let alone what programming do you offer once people come in the door. We worked with different collaborators in the neighborhood to discuss the various forms of barriers that exist for long term community members in the Lower East Side, and we’ve been especially focused on making sure that this continues to be a neighborhood that community members recognize and feel welcome in.

Can you tell us about the CETA jobs program and particularly the Cultural Council Foundation (CCF)? What impact did this program have nationally and locally in New York City?

MG: CETA was federal jobs and training legislation enacted in 1973 by Richard Nixon. It existed through the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations and then was defunded at the beginning of Reagan's presidency. And the idea with CETA was to decentralize and distribute money from the federal government to the states and localities, to what were known as “prime sponsors.” Some of this was to do with Nixon’s goal of shifting power from Washington D.C., but CETA’s architects also recognized that local places may have a better sense of what their actual labor force needs are. [What] their economic development, skills innovation, and community needs [are]. An important detail is that while there were many, many titles under CETA, none of them addressed artists specifically. It was never intended for artists, but using Title VI, which was public service employment, meaning job placements working in the service of the community, of the public, artists were able to get funded for projects through CETA.

JW: For those who know less about what was happening economically in the 1970s, part of the intention, or part of the reason that this conversation even happened at the federal level was that the United States was facing a significant unemployment rate and rising inflation. And so the legislation was developed to address both of those concerns simultaneously. I think it's important to understand what the federal landscape looked like, if only to know how similar it is to today, and why this is an important conversation to be having right now.

This was also the moment when New York was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy; the city was contracting culturally in many ways, and as a result, a lot of the arts and cultural programming was being reduced or eliminated. There was a huge divestment in communities of color. That was actually around the same time that the school building in which Artists Alliance is based was decommissioned from the Department of Education system. And so I think it's helpful to understand just how immense the economic and cultural needs were throughout the country and from the perspective of this show, particularly in New York, to understand what the artists, administrators, and community partners were getting into when they accepted the CETA positions.

MG: The Cultural Council Foundation (CCF) was a pre-existing private non-profit service organization, sort of a fiscal agent, for community cultural organizations, on whose behalf they received and managed grant money. Sort of a bank, bookkeeper, and parent for those organizations if you will. When CETA in NYC were made available to artists, the CCF won the contract to administer what became the country’s largest CETA-funded arts project, with 300 artists and a $4.5 million yearly budget.

The thing that I think is very critical is that CETA was a jobs program, and not a grant program. The jobs were not necessarily meant to be forever, but it was a job. These employees got a living wage and benefits: vacation time, health care, etc. What's interesting is that New York City was one of the last places to get a CETA Artists Project and that was not because there wasn't an immense effort for years on the part of the cultural community, but it’s important to underscore that the infrastructure and the political effort, including from the CCF, to get CETA money for artists in New York was incredible.

The people who were the architects of the CCF CETA Artists Project worked very closely with the federal Department of Labor, with the NYC Department of Employment, and with the Department of Cultural Affairs which had just come into being as its own separate agency, and the program required a lot of political buy in from the city administration. From Mayor Abraham Beame, from Henry Geldzahler, the Commissioner of Cultural Affairs at the time, and Assistant Commissioner Cheryl McClenny. She was really instrumental in creating the structure of the CCF CETA Artists Project along with CCF Executive Director Sara Garretson and Ted Berger, the Director of NYFA, who had been working as artists in the schools coordinator for New York State. He was very involved in trying to help people look at issues of arts education, the role artists play in communities and in schools, which was very relevant to CETA. And so the CCF CETA Artists Project is very special in this way because it was so intentional and so cohesive, comprehensive maybe, even in its naissance. And it was huge with 300 artists employed in the first year and 325 in the second. The entire administration were also artists, so they really understood artists' needs as workers and as creatives.

JW: It’s also important to understand that it was not a granting program. This is an issue that has come up in post-pandemic economic recovery quite a bit. Grants are not the only mechanism for supporting artists. It was a critical moment where the practices and labor of artists was understood to be a part of workforce conversations.

The legislation was not developed to specifically call out the arts community. It was not at all dependent on arts agencies to come on board, although at the local level, it became very dependent on those lines of support. But really, it was a shift that has happened before, but it doesn't seem to sustain itself, where the labor of artists is understood under larger conversations of labor. The idea during this period of time was to create publicly-funded jobs so that eventually the private sector, given some time to recover, would be able to pick up these employees. The intention was to continue to allow the public and private sector to work in tandem with one another.

I think those are critical elements for people to understand that are often outside of the usual arts-specific or arts sector conversations. But they are the factors that created an environment that allowed something like this to happen, which hadn't happened in forty years, and forty years later, hasn't happened again. And so understanding the parts of other industries or other lines of communication that lend themselves to a successful interpretation of sustainability in the arts sector has been really important in the process of not only developing this show, but also thinking about what we might identify as a potential positive impact that this exhibition can have, and generally speaking, this larger project can have.

And in terms of how I became familiar with the project, I was, of course, introduced to this through Molly and City Lore. It sort of came to us because of our previous work at Cuchifritos with artists who were former or current members of the collective Colab. And in 2014, we, along with a number of different spaces throughout the LES, remounted Colab’s Real Estate Show, which had happened several decades prior. It addressed the gentrification of the Lower East Side and asked artists to respond to the political and social conditions of a neighborhood in transition.

The project demonstrated the ability of creative practices to instigate critical conversations about where we are as a society and force a certain amount of reflection. This throughline in much of our exhibition programming made the CETA project all the more right for us. It has allowed us to bring clear and concise questions around labor – an issue the pandemic has put a fine point on – not only into our gallery but to reflect on them within the larger space of Essex Market. Having been a part of this community for over 23 years, our work often considers the intersecting realities of creative practice, daily habits, and the economic precarity of our community. Anna Harsanyi's project In, Of, and Crossing Essex thoughtfully mined these issues in 2018 as Essex Market prepared to move into the new building.

MG: As human beings, the lived experiences of art and all of those other aspects of daily life are all completely connected. And that's what's great about Cuchifritos is that they embody that. And I think that for us, that was really exciting to be able to work because Jodi is so keyed into that and so much of the work that they do is about that.

The CETA program didn't just put artists in an arts context. They put artists in all kinds of contexts, in correctional facilities and medical facilities, in public spaces, in senior care centers, in youth centers, in any place you can imagine. So it wasn't explicitly about enhancing the arts ecology. It was about giving work to artists and helping the public understand the value of artists' work. And just as a sort of example of this, one of the CETA artist Marc Levin who is a filmmaker, documentary producer, and director. At the time, one of his assignments, along with the CCF film group subcontracted through the Foundation for Independent Video and Film, was making a documentary for the Bread and Roses program of the 1199 Health Care Workers Union. The Bread and Roses program was founded by a man named Moe Fonerowner who really believed that workers are entitled to the full complement of benefits that humans require to not just survive, but thrive. As the poem goes, give us bread, but give us roses, too. We have to eat and stay healthy and housed, but we also have to be expressive, culturally-grounded, sentient beings, and these things are completely connected and overlap. And the Bread and Roses documentary that the CCF film crew made records some artists performing and engaging with union members, in situ, in the hospitals where they worked, in the union halls where they met. Artists and cultural workers helped to foster conversation, supported them, and reflected the workers’ own lived experiences through oral histories, plays, and other expressive arts engagements. At the time many community hospitals were under threat of defunding and closure. So it was that services and jobs were being removed from the community, and Bread and Roses helped to reflect both the workers’ struggles and their value, and provided an outlet for their voices. It also served as a buoy during tough times. Bread and Roses was itself at least partially funded through CETA Title VI during that period.

And so it really comes all together, labor, culture, and community. And at that time in the film, in 1979, they're referring to the medical workers as essential workers. Talking about the exact conversation that we're having right now about frontline workers, and you see the support that's going back and forth between the artists and cultural workers and the workers in the 1199 union. And it's incredibly inspiring – it could be right now. And so I think that's really important. We, especially in the U.S., tend to silo art and culture out. And CETA was a way of proving that that was not only counterproductive, but that artists belong in these contexts, as workers.

I love the title of the exhibition blurring artwork and ART/WORK because I think it really points to what both of you are saying about how art isn't separate from our daily lives and all the things that we're going through. Art is also subject to the same forces and vice versa. The larger question is how we consider labor, how we work. What do you envision as a support system that can actually work for artists? What do you dream for the future of our sector as we work towards a world that supports artists better?

JW: I think about this all the time, and I firmly believe that if we as a sector want to progress we have to ask ourselves these questions in earnest. We need to look at the issue holistically, and understand that in order to create sustainability around the work that's already being done, to create seriousness around the work that's already being done, we have to consider the perspective of industries that are perhaps less familiar with the cultural field.

We really need to think about the entire arts ecosystem and not how we solve it for artists or how we solve it for curators, or how we solve it for institutions. It could be difficult and uncomfortable to unpack and be honest about our own value systems around work and labor, about what is produced within the sector itself.

I've been really fortunate to be in touch with people who are asking these questions in ways far better than I can. These conversations have been happening well before the pandemic, though the pandemic obviously put a certain amount of urgency around these questions, and perhaps brought attention to them to a much broader group of people. We have to come together as funders, as individual practitioners, as institutions, and as alternative arts organizations to ask ourselves what is work in this field, what is essential work in this field? And understand that a lot of the freedoms that are afforded to many of us by being unaffiliated with institutions can be great in the short term and very damaging in the long term.

What are the ways that we can operate communally and collectively as a sector to make sure that everyone is cared for in their basic human needs? The 2021 project Drawn Together offered a process to specifically address this question. I think what was so exciting to me about CCF when I was introduced to it was that (while it might be very unsexy when someone comes to the exhibition and sees this) we even have someone's health insurance policy on display in a case, treated like a valuable piece of material, because it represents an even more valuable gesture that the whole human being needed to be cared for by this program. And that was an obligation.

Something else we didn't get to mention about CCF is that they went to bat for the artists who were hired into the program to ensure that they maintained ownership of some portion of the copyright over the work that they created through the programs funded by CETA. Again, this could appear very unsexy, but it’s absolutely critical, especially that in an employment program one gets to own their work. It's even still a bit of a novel circumstance, but if we're hiring artists in this workforce development program with the suggestion that they will be able to use these skills for future employment, it is absolutely necessary that they retain copyright over their work and continue to own it and build portfolios and income off of it.

MG: And a thing that was very unique to CCF is that they gave artists one day of the five day work week for their own work. While we've emphasized the importance of not separating culture out from other sectors and other systems, we also want to make sure that we underscore that the CCF program understood that there is value in artwork and making art in a studio for oneself and as a benefit of artists to society in the creation of work, and that process is equally valuable to the public service employment aspect and that it's a balance of those that they did and had to strike. But that's an important part of what we're trying to have people discuss is that artists inherently bring incredible value to society, to expression, to being able to know and understand and hopefully care for each other and that that was embedded in that program. And that was a unique thing.

JW: In terms of what would be a dream future, it's honestly really hard to say because I think I myself have to answer some of these questions as much as anybody else does. But I do think that we're in a particularly important moment where a tragic, urgent, traumatic recession triggers a groundswell of support, and then there is a period of recovery that comes after. Often in those periods of recovery, the amount of support that is extended during the moment of urgency begins to recede. And I think all sectors have seen that throughout all time; it’s something that the arts sector is particularly aware of as a pattern. A lot of the advocacy efforts and a lot of the political will have to come from a sustainability approach. And I suspect that's true of most economic problems that America needs to resolve. But we really need to understand that we can't continue to put a bandaid on it if we want to make lasting change, if we want to integrate the arts into a lived experience, we need to start advocating in a different way. And that might mean educating one another on the roles we play and having conversations across disciplines, across positions, across institutional lines.

ART/WORK: How the Government Funded CETA Jobs Program Put Artists to Work is on view at Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space until March 19, 2022 and City Lore until March 31, 2022. To read more about how the cultural sector is rethinking its relationship to capital and labor, also read our interview with Nati Linares and Caroline Woolard.

About Sophia Park

Sophia Park (she/her) is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn, NY and Gumi, South Korea. She received her B.A. in Neuroscience from Oberlin College and M.A. in Curatorial Practice from the School of Visual Arts. Recently, she worked as a curator for the 15th Gwangju Biennale. Formerly, she worked as the Director of External Relations at Fractured Atlas, a national nonprofit arts service organization and taught entrepreneurship and the arts at New York University. She is part of slow cook, a curatorial collaboration with Caroline Taylor Shehan where they make programs and books, and is a co-founder of Jip Gallery (2018 - 2022). You can probably find her running some silly distance, trying to get back into tennis, or dancing somewhere.