By Courtney Duffy on November 11th, 2015

What Last Week’s DMCA Exemptions Mean for Artists: Part Two

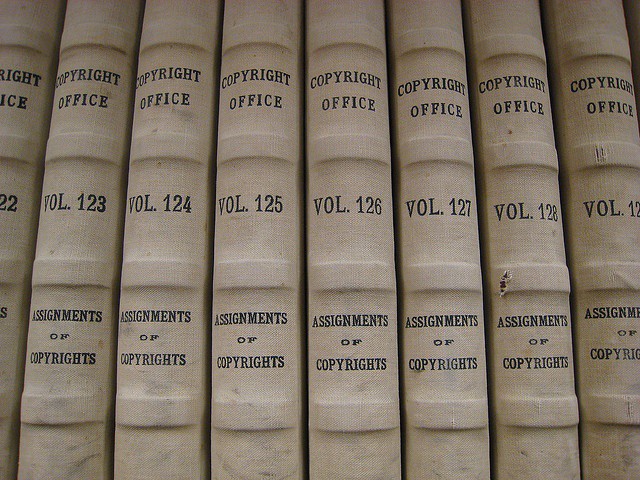

Last week I published a post on the Library of Congress’s process of reviewing exemption petitions for the anticircumvention measures contained within the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). The procedure, which takes place every three years, culminated late last month when the decisions were handed down. A Fractured Atlas member organization, Kartemquin Films, petitioned for an exemption on behalf of the filmmaking community.

I spoke with Artistic Director and founding member Gordon Quinn to get his take on the decision.

What is Kartemquin’s DMCA backstory?

Every three years, we have to renew the DMCA exemption for filmmakers. Jim Morrissette, Kartemquin’s Technical Director, and I are part of the team that goes to the Copyright Office to do that. Jim’s technical knowledge has been vital in explaining why filmmakers can’t be forced when making fair use to use materials from inferior formats when producing their work for theatrical or broadcast distribution — a key issue now with the era of Blu-Ray and streaming video on demand, and beyond.

You and the Kartemquin team first petitioned for an exemption in 2011. This year your petition had a few changes. Can you explain how it has expanded over the last few years? What are the key takeaways from this year’s exemption?

When we argued for Blu-Ray three years ago, we didn’t get the exemption. This time we clarified some language here and there, but the biggest difference was we included Blu-Ray again and won. I had just finished my film A Good Man about Bill T. Jones, who talks about white bodies looking at black bodies and you can see the muscles rippling under his skin. You need that quality to see all the detail that was in that original image to be able to critique it properly. For certain documentaries, the highest possible fair use is critical.

Jim Morrissette made a spectacular presentation on Blu-Ray at a Copyright Office hearing in June — he came with a number of clips and showed them the difference. He shot down pretty decisively any suggestions that you don’t need to access to it as a filmmaker.

The Library of Congress did not give you everything you wanted, though, as in the case of narrative filmmaking. Can you explain?

Kartemquin doesn’t make narrative films, but the Copyright Office’s decision to exclude narrative films from the exemption was certainly disappointing. Narrative films are part of American culture and you can’t lock up a part of the culture. If I’m a narrative filmmaker, I also want to be able to critique and parody and put our culture into context. What was unfortunate about that part of the decision is all we’re asking for with the DMCA is relief for it being illegal to break encryption. The actual use we’re making is legal. The Library of Congress was saying, well, there’s a difference with narrative filmmaking.

A recent court case contested fair use in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris — a character quotes a line from a Faulkner book: “The past is not dead. Actually, it’s not even past.” This line is also the opening title of our film Stevie. Although we never got sued, Woody did, and he won — which he should have. You can’t lock up the culture, you have to allow people to criticize, critique and comment on the art.

Despite the narrative filmmaking setback, this exemption was a win on the whole for Kartemquin and filmmakers alike. That said, the process still required time and resources, and will do so again in just a few years. What changes would you like to see to the process?

My short answer is: This law never should’ve gone through in the first place. It was kind of written by the lobbyists for the big rights holders. It creates a huge burden for all kind of classes of people: librarians, documentary filmmakers, narrative filmmakers, people who make ebooks and more. It curtails our First Amendment rights. The Copyright Office, to its credit, understood that this was an unfair burden and created the exemption process to offer relief for that.

What about some other fair use-related issues that challenge filmmakers? Can you describe, for example, the process of licensing music for films?

Licensing music that should be fair use is an unfair burden; licensing music that is not fair use is expensive. We claim fair use when we are transforming music into something new. But we also use music as music and we license it.

When we did Hoop Dreams over 20 years ago, I had to license the elevator music that played in a hospital scene because I couldn’t get it shut off while we filmed. I also had to license the Happy Birthday Song* for considerable money for the theatrical release. In our film Refrigerator Mothers, we wanted to use a song by John Lennon in a way that was clearly not fair use. The producer convinced Yoko Ono, John Lennon’s widow, to watch the film. She said she wanted Kartemquin to have the song and whatever we paid was fine. It has taken time, but we’re finally able to stand up to the big guns like Sony, Fox and all the big companies and rights holders who threaten to sue people.

*[Editor’s note: The ownership of the Happy Birthday Song has since been challenged in court. This recent blog post has the details].

Are there any resources filmmakers can turn to if they have questions about fair use?

The first thing they should do is go to the Center for Social Impact. They have tons of resources* for filmmakers.

*[Editor’s note: Here’s a sample set of CSI’s resources for filmmakers.]

- Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use

- Documentarians, Fair Use and Best Practices

- Fair Use Teaching Tools

What’s next for Kartemquin Films? Any interesting projects coming down the pipeline?

We have a record amount of films in production and several new films that are about to be released. Our award-winning film Almost There, following the filmmakers’ discovery and caretaking of an outsider artist over eight years, comes out in select theaters and VOD next month. We have a short, On Beauty, which comes out on DVD in 2016. Additionally we have a film called In The Game that is about a women’s soccer team at a low-income high school that has just been playing festivals. Finally, we have a film called Unbroken Glass that is about mental illness in an immigrant family and should be finished later this year. Additionally, we have a film called Raising Bertie coming out about three African American boys coming of age in rural poverty in North Carolina which will be finished in early 2016.

And then, of course, there’s more coming for 2016, when Kartemquin turns 50 years old.

Stay tuned for my next post on the Library of Congress’s DMCA exemption decision on another industry that impacts artists: 3D printing.

This post was lightly edited for the sake of brevity.