Seeding Collaborations: A Conversation with Michael López and Karl Orozco

For this Seeding Collaborations, we spoke with artists and educators Michael López and Karl Orozco who founded and run Risolana, a community risograph studio located in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Risolana’s name is inspired by the New Mexican concept of la resolana, which is a south-facing wall where community members can gather together. Risolana offers public access to a risograph printer and runs a range of educational workshops and programs highlighting the potential of the risograph as a medium and tool for artistic and social change.

Starting from the beginning of their work together, López and Orozco shared a view into how Risolana’s programming is created and informed by their own practices as artists, creatives, and educators. They spoke to the practical challenges of sustaining their work and how they are navigating them—balancing an art practice with all the other things they’re facing.

Sophia Park (SP): How did Risolana come to be? How did you decide to work together?

Karl Orozco (KO): I used to live in Queens, New York City and then moved out to Albuquerque in July of 2020 to work as a full-time high school art teacher. My practice is community oriented, often social practice-based work that revolves around print, video or installation. I've always been interested in risograph (riso) as a medium. I played a lot with silkscreen printmaking in college and other forms of relief printmaking, and knew about the process but didn't really get a chance to work with it in NYC. I’ve always admired work made in riso that I saw, especially books and sequential-based work.

In early 2021, when my wife, Isha, and I were working on a graphic novel called prep school, we searched for a small or independent press to print in Albuquerque, ideally that printed with a risograph. Michael was one of the reasons why I moved, as he connected me with the job that I have right now, so I asked him if he knew of any riso presses or publishers in Albuquerque. There were none at the time, but Michael had received this fellowship funding from the Academy for the Love of Learning that was specifically intended for a community based art practice, which got the ball rolling for us to think about Risolana and how it could be a space for both prints, education, and community building.

Michael López (ML): I also make work similar to Karl. I like to make work that involves collaboration and the surprise you get when you work with various people who have different understandings of art practice. A good example of this is when I built a trailer from scratch while living with my sister when I returned to Albuquerque. I applied for a grant for it to become a temporary public art work and invited artists to make work and perform in the trailer. It was both an artwork and a way for me to save money to sustain my art practice.

I've always been interested in platforms and spaces. I moved back to Albuquerque to work at Working Classroom, an after school arts and visual art theater program. It was the organization that raised me in the arts. I met Karl there; he was invited to teach a workshop and just blew everyone away with his brilliance as an artist and a teacher. I was working on a project with Three Sisters Kitchen, which is a community organization in downtown Albuquerque. We were working on this project called Nutritional Values, collecting stories from different community members around New Mexico. Like Karl, we were looking for a place to print some of the stories or to print some of the collateral to advertise. Risograph had been coming up as one of the mediums we could potentially use. It was an incredible coincidence that we were researching risograph studios in Albuquerque simultaneously, and couldn't find any accessible spaces.

When neither of us found a space, we both said, “well, let's just start it—we will make the space!” Risolana is a personal investment and it sprouted from projects we were personally working on at the time. Karl and I did this partnering exercise where one person talks for 7 minutes while the other person listens. A third person is there to be an observer. We took turns talking about what Risolana would mean for us before we even bought the machine. It felt like there were a lot of connections between ourselves as educators, artists, storytellers, and visual artists who want to share in that excitement.

Risolana is located within Partnership for Community Action’s (PCA) social enterprise center, which played a big part in our start. I was documenting the construction of the building at the time and had worked with them before. When I reached out to them as they were building this brand new social enterprise space, they welcomed us with open arms. This has also made a big difference for us to have a space where we could be rooted in community.

SP: Can you ground us in what the studio looks like? What equipment and material do you offer to those who come to use the space?

KO: The big one is the risograph printer. Specifically, we have a pretty recent SF5450 model with a single drum that can print up to 11” by 17” and anything smaller than that.

ML: The colors we have are black, sunflower, fluorescent orange, flat gold, cornflower, fluorescent pink, light mauve, federal blue, green, and scarlett. Karl would suggest the colors, we would talk about it, and then decide. With the artist-in-residence, Lena Kassicieh, she suggested fluorescent pink because it's her favorite color and uses it in all her art. So in response, we added fluorescent pink and then this process was folded into how we choose new colors. This year, Carmen Selam, our new artist-in-resident chose light mauve.

KO: We have a lightweight binding machine and an industrial paper cutter from the eighties. We also offer a limited range of paper, including colored cardstock and regular white paper in different sizes. We're situated in a boardroom used by PCA. By day, the boardroom is used for meetings between various community partners. In the afternoons, evenings, and weekends, that space is usually free. That's our agreement—we’re mostly there during those times.

An image of a large range of artwork from prints to zines created in Risolana on the walls of the space. Image courtesy of Risolana.

ML: We also have tons of art on the walls, all of which has evolved since the beginning of Risolana. We use magnetic panels to make sure we can have artwork up. Because we are a community art space, we want to make it easy for us to be responsive to what people are creating in the community, and for the art to circulate. In the past year, we've amassed tons of books but we've been making books since the beginning.

We have some other materials like binders of color samples, hole punches, and long neck staplers. We're outfitted for any person to come use the space. It’s a beautiful thing to witness: at night, when we have bigger projects, people are collating together at the table. The space is completely filled up with all of this incredible work and then the next morning—it's like we weren't even there. I haven’t been in a studio setting in a really long time where you have to clean up really well after you finish a project. It creates a different dynamic. Some good, some bad. But for the most part, it feels really nice to see people come in, collate, and then take everything home by the end of the day. Another thing I want to point out that's actually a big thing for educational purposes is that PCA has big televisions screens available. Karl plugs into the computer and does live designing sessions for people. It's a really nice tool for showing people everything that goes into making a good riso print. It's not just about the printing itself, it's also about the design and the file setup.

SP: As you mentioned, education is a big part of Risolana and your own practices. Can you share how the programs you’ve developed are influenced by your backgrounds as educators?

KO: Michael brought up that in the last year we've gotten way more complex, mostly book related projects. The prints themselves are also growing more complicated in a good way. One thing that I always think about as an educator is scaffolding. When teaching a group of students something new, scaffolding works to build a foundation of simpler concepts, which build with more technical skills with the goal of creating something that over time is more fulfilling, complex, and layered. When we were first starting Risolana, one of the first things we realized was that unlike a place like NYC, where there are many artists who already have some experience in riso or perhaps other really related mediums, here in Albuquerque it would to take a little bit more time to get people familiar with riso.

For the first two years, a lot of our programming was based on getting people into the space and showing them what the machine looks like, how it works, and how you can design for it. The main program for this era was Thirty Under Thirty (30/30), where 8 to 10 people would come into the studio every month. Most of the time, they had no experience with riso and that's okay. We would tell them that we’re here to show you what’s possible and to give you one way of thinking about riso for the future. This has worked really well. We still get new people coming in. Over the past year, a lot of those people that came for 30/30 have been able to build off of that foundational knowledge and make something else that is really utilizing the riso in a way that's tailored to their practice, which is also exciting and pushes the boundaries of riso.

ML: 30/30 is hyper affordable for what it is. For $30, you get 30 prints on nice paper with access to multiple different colors because we want them to walk away with something they can look at that continues to be a teaching tool and reflect on their experience. To have access to designers in the space who really understand the back end of planning for a riso print is really exciting to watch because I'm personally not a designer. I know how to use some of those tools, but our programmatic supporters Carlos Gabaldon (Lab Tech), Amelia Johnson (Project Manager), Karl, and Katrina Noble, Malcolm (yaudi.xyz) are all very well versed in that. They ask people, “What if you tried this? What if you color separated this way? What if you did this trick with the layout to get more out of your print?” How often do people get to have a one-on-one with a professional designer for that little amount of money? To watch other people go through that process is really exciting.

I also think that there's a lot to be said for being inspired by one another and creating spaces for that. In terms of education, a program in its pilot stage is called Along the Way, which is influenced by the culture of riso itself. There are a lot of people who own a riso studio and when they're taking a trip, they’ll visit local riso studios. The culture of riso studios is to be very open. We are pretty volunteer-led and don't have normal business hours, but something that came up was being responsive to the amount of talent that's coming through Risolana as a resource, and finding ways to share that out to the local community. The program is framed as a demo—if a person's traveling through or if it's a person who's from here, they want to do a print project and we can make it worth it for us and for them and for the community. I see it as like an “all boats rise” or “everyone wins” situation—we frame their print project as a demo. As part of this framing, they get to print for free in exchange for sharing their process plus a donation run of the prints to give to people at the end. They take home the percentage of the run that they wanted to make in the first place.

While client work has slowed down at the moment, we have a number of workshops planned at University of New Mexico (UNM). The client work subsidizes a lot of the community work we do. When people do a print job with us, that's still hands-on learning. We're reinvesting that client money in community workshops.

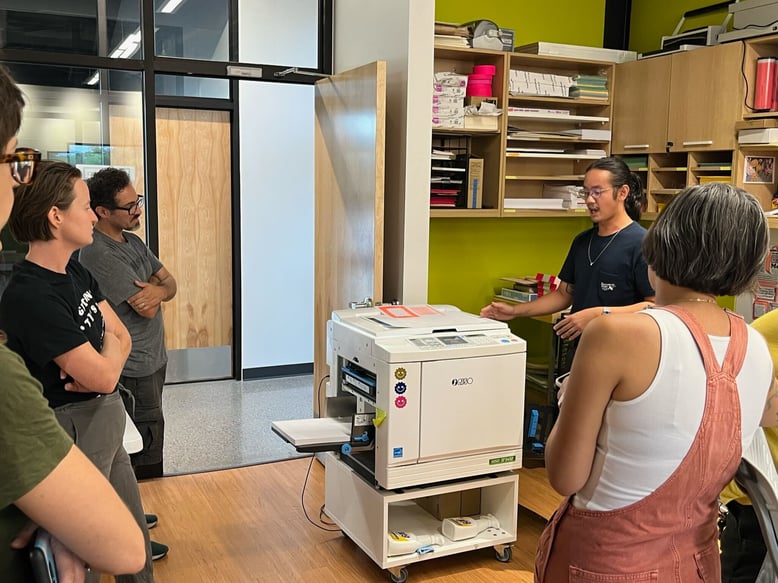

A view into an Along the Way workshop with Nat Center. Image courtesy of Risolana

A view into an Along the Way workshop with Nat Center. Image courtesy of Risolana

SP: What I appreciate is this attention towards circulation, which is already rooted in the history of the risograph. To reach any community, there is sort of this circulation and passing-on-ness that has to occur. Can you describe your audience to us? How does your audience relationship shift within the context of New Mexico's reputation for being rich in art and culture?

ML: Our audience is interesting. I was surprised with how many people articulated how much Risolana is a resource for meeting people in Albuquerque outside of the context of a bar or art shows. The art scene is really vibrant in that way—people can display their work in a variety of art spaces, like Santa Fe and Canyon Road types of venues. Risolana operates more as a makerspace for art. It feels like we're very unique in that regard.

Many people are also activists and storytellers. I think we exist in the art world in an active way because of the connections between art and food, culture, music, and dance. In a lot of ways, our audience is composed of people who aren’t interested in printmaking and lithography alone. There are poets and farmers in our midst.

New Mexico has a lot of people who move here from other places. It also influences our audiences. Many people have been a part of art spaces in other cities—like San Francisco or New York. I see that they're looking for similar types of communities they had in other cities. This process is slowly and steadily connecting people who aren't from here to people who are from here. For example, Carmen Selam, our current Artist-in-Residence who's from Yakama had a serendipitous moment with another artist recently. An artist named Jason Garcia, from Santa Clara Pueblo, had never made a comic, but was really inspired by Carmen creating a comic book. He's made things related to comics, like ceramic covers of comic book concepts, but at Risolana he had the opportunity to experiment. While Jason was making a print at Risolana, he saw a proof of Carmen’s book.

He went, “Oh, I'm going to text this to Carmen.” And I said to him, “She hasn't even seen it yet!”. I love reflecting on those connections—people sharing in the excitement of the work they're making at Risolana, and unknowingly inspiring people’s future work. I think there's something quite beautiful there—that idea of inspiration and exchange.

KO: I think riso's still kind of a niche thing. A lot of people that knew about riso were folks that were already in the arts. In our first six months of doing 30/30, for example, many people were already printmakers or artisans or studying at UNM for an MFA. A broader reach is exciting because it will push the medium forward and keep it relevant. I think Michael has been really good and intentional about broadening the reach of riso through his connections in client work or other projects with people, where the cost is either very low or even free. The work he does with people outside of the sphere of New Mexico resembles pro bono design work.

Broadening the reach of risograph and Risolana also happens through workshops like Typesetting the Movement, which is “designed for New Mexico’s activists, movement builders, and community leaders interested in signage as a tool to unite people, amplify voices, and disrupt power.” We want the risograph to be a tool for social and political action. The concept of teaching this as a workshop took over a year to develop. It was originally based on the idea of using the riso and paper cutouts of type fonts to mimic how you would create a letterpress print. This was an original concept of using the riso specifically for typesetting. Through a lot of conversations, Michael and I were able to develop it into a workshop that was specifically for people in the movement, community builders, and political activists. That felt like the moment where we began to see what sets us apart from most other risograph studios:investing in community and giving people the tools to empower them. We work with a lot of different strands of Albuquerque and it's very exciting. It's hard work, but it is very exciting to serve as intermediaries for so many different spheres of life here.

ML: I want to add to that for the Typesetting The Movement workshop, it’s free and we explicitly reach out to nonprofit community organizations first. We see it as an investment in people learning a skill set, one that they can put to use independently. We say, “hey, if there's a rally or a protest or you need to make some brochures or something, let us know.” We're a hands-on studio space. The empowerment comes through people learning how to use the machine, and having a technical understanding of what needs to happen in order to get the print that they want to see. That's what we are working towards every time we run this workshop—for people to understand riso better in order to use it when they need to use it.

Karl Orozco leading the Typesetting the Movement workshop with attendees. Image courtesy of Risolana.

Karl Orozco leading the Typesetting the Movement workshop with attendees. Image courtesy of Risolana.

SP: I really appreciate your lens towards learning and adaptation in programming. How do you think about caring for yourselves as you also care and tend a community and help and give tools for the community to grow? The question of work-life balance is hard to answer for artists because of the difficult relationship between life and art, right?

KO: I'll be very real—I love teaching. It's just the thing that I feel that I was put on this earth to do. And I teach full time. While I get so much fulfillment out of the work that I do, it is pretty hard to maintain myself on top of a full-time teaching job. Especially this school year, I've been feeling like I don't know how sustainable it is for me to be able to do everything. Prior to this year, I was more hands on with both leading workshops and navigating the organization. On top of that, it’s not my first year at the school that I’ve been teaching. One thing that I want audiences to know about being an educator and teacher is that when you get better at teaching, your workload doesn't lighten, you actually just get more types of work. I also pride myself on being a really great teacher, and students will gravitate towards those teachers that are really invested in them. So while the classroom things like planning and grading get smaller each year, it's that extra stuff that will always take up the time of a teacher. I love it and I'm fulfilled by it. But I've realized recently that this full-time teaching job probably won't give me more space and agency for non-paid work. It’s a little bit of a harsh reality that this kind of work—service and volunteer work—can’t sustain me. I hope not to bum people out, but I do think it's necessary for people to understand the nature of our work. And to normalize saying, “I don't know how sustainable that is for me personally.”

ML: My hope is for an angel funder to donate 2 to 3 years worth of funding to pay for Karl to be a full-time educator at Risolana. To Karl’s point, I've stepped more into this role of managing the space as a volunteer. I'm always straddling these weird areas. I make a point of maintaining hands-on work, because it makes me a better producer and director. I've worked for people who had no background in making, and noticed a lower level of care towards the makers and builders because they don't have any empathy for what it actually takes to make. That's why I tend to also work on personal projects through Risolana. Similarly, Karl's worked on multiple exciting projects. Carlos likewise has done some stuff. What refreshes me the most is when someone comes to me with a project and I can say, “let's just do it.” Not needing to put up with some of the bureaucracy of finding funding to make something is really refreshing. Connecting around an idea that a person has for an exciting project—it’s part of the gratification of riso as a medium. Sometimes when you're in an institution, things take way too long and the creative process can be stymied by all of the roadblocks between you and your goal. Sometimes those blocks are important, but sometimes someone just wants to print a band poster.

My daughter is three years old and recently made her first zine for Abq Zine Fest, first with her mom. And it was just the most adorable thing, seeing her engage in trading with people. When I ask myself why am I doing this, the thing that always brings me back on a heart level is that I love community work and I love working with people in this space. I love working with really talented teachers like Karl. I love working with talented designers and artists like Carlos and artists. It inspires me to be around this energy. That said, I had a kid when we started this and it was a pretty intense time for me personally and professionally. But even this brings me back to Risolana and makes me feel really invested in it because I want my daughter to experience a space like this. I really enjoy it when she's here—she even helps sometimes when I'm in the studio space! There's something about a young person being in a creative space around creative people that I think is just really enriching. I think that's the selfish part of why I continue.

The trade off is that there’s unexpected labor and sacrifices. There have been days where balancing work with Risolana commitments left me without enough family time. There was a feeling of guilt. But listening to and trusting the people you're working with and trusting their investment in the project helps me stay grounded. Recently, Karl was like, “We have so much going on right now, do we really need to do 30/30?” I think it's nice to have people ask you those questions. Do we need to do this? It's an event. Having people help you prioritize and simplify or even push you a little bit is also really nice. At some point, just taking a walk or going out to lunch and remembering we’re people, not an organization, you know?

Thank you to Michael López and Karl Orozco for joining us for this conversation. Seeding Collaborations is a series focused on archiving and highlighting practices across the arts ecosystem that are thinking differently about how we live and work as a cultural sector. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

About Sophia Park

Sophia Park (she/her) is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn, NY and Gumi, South Korea. She received her B.A. in Neuroscience from Oberlin College and M.A. in Curatorial Practice from the School of Visual Arts. Recently, she worked as a curator for the 15th Gwangju Biennale. Formerly, she worked as the Director of External Relations at Fractured Atlas, a national nonprofit arts service organization and taught entrepreneurship and the arts at New York University. She is part of slow cook, a curatorial collaboration with Caroline Taylor Shehan where they make programs and books, and is a co-founder of Jip Gallery (2018 - 2022). You can probably find her running some silly distance, trying to get back into tennis, or dancing somewhere.