By Ian David Moss on July 10th, 2014

Fractured Atlas as a Learning Organization: As If One Bottom Line Wasn’t Enough

(This is the fourth post in a series on Fractured Atlas’s capacity-building pilot initiative, Fractured Atlas as a Learning Organization. To read more about it, please check out Fractured Atlas as a Learning Organization: An Introduction.)

Many a social enterprise measures its performance via a double bottom line. The terminology comes from for-profit accounting, where the “bottom line” means the total profit or loss for the company. A “double bottom line,” then, includes not only this barometer of financial performance but also a measure of social impact. The unit of measurement for financial performance is easy — it’s just dollars (/euros/yen/whatever currency you prefer). But what should the unit of measurement be for the “other” bottom line? This is a question that’s bedeviled thinkers in the social sector for decades.

In our last post on making decisions in an environment of uncertainty, we considered the situation of a hypothetical arts organization considering whether to accept space rentals later into the evening. We performed a cost-benefit analysis using a Monte Carlo simulation, and illustrated how, with the help of just a few variables and simple calculations, it’s possible to estimate which choice will lead to the greatest financial benefit for the organization. I wrote “financial benefit” up there just now for a reason. The field of decision analysis, from which the modeling techniques discussed in the previous post originate, comes from management science — in other words, the sort of stuff they teach people in business school.

Most of the decisions that businesses make are, at some level, about money — which means that businesses have it comparatively easy. The decisions facing a nonprofit, however, are usually more complicated than that. Yes, of course any institution cares about making sure the bills get paid…but hopefully, our ambitious extend beyond that. Arts organizations need a way to make decisions that takes into account mission goals as well. But what are those mission goals, and how could one possibly describe them in terms as concrete as dollars and cents? Fortunately, a tool I’ve written about before comes in very handy here: the logic model.

Yes, that’s right, the much-maligned logic model turns out to be the crucial missing piece necessary to transform decision modeling from an abstract exercise into a day-to-day management tool. To review, a logic model is a tool for laying out the components of a strategy and describing them in a structured way, so that the rationale behind your or your organization’s decisions is clear. It could be used in virtually any context, but in practice it has most often found adoption within the nonprofit and global aid sectors to describe the charitable and programmatic aims of an organization or initiative.

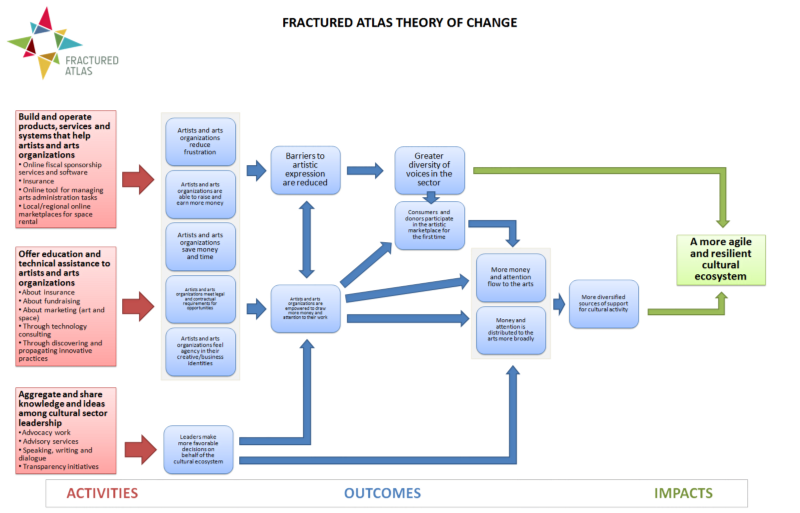

A theory of change is a kind of intellectual cousin to the logic model that lays out in more detail the progression between your activities and the impacts you hope to achieve. One of the great benefits of developing a theory of change in a decision-making context is that it forces you to articulate with a great deal of specificity what a better world would look like and how your organization would help make it happen. This specificity comes in handy when it’s time to develop measures for mission success, which are a key component of many logic models.

And once you have mission success measures, you can use those as a benchmark for defining successful decisions, the same way you could use money.

How does this work in practice? For a very simple example, take a political campaign. The strategy might be multifaceted, but the measure of success couldn’t be more straightforward. Every decision that the campaign makes theoretically should be evaluated through one lens and one lens only: does this action increase the odds that our candidate will win? Now, a lot of times, there might be more than one success factor to consider. In fact, there might be a lot of them — the Strive Partnership, an educational infrastructure initiative in Greater Cincinnati, uses (and measures) 53 separate student outcomes!

Most of the work we do in the arts won’t be quite as complicated as that, but for many organizations one metric may not be enough to get the job done on its own. In Fractured Atlas’s case, we ended up choosing a few metrics for our mission success. But before I share what they are, I want to tell you a little bit about how we developed them. Descriptive vs. Aspirational Over the past eight months or so, we’ve engaged in a parallel process to develop theories of change and associated logic models for every program at Fractured Atlas, along with one for Fractured Atlas as a whole. The programs came first. I interviewed each program director and members of her staff to get a concrete sense of our day-to-day activities in each area. Through several iterations, we developed a model for that program’s goals and its strategies to meet them. As we were finalizing those models, I looked for patterns and themes across the programs that I could then start to use as a foundation for the “grand theory” for Fractured Atlas as a whole. I call this the “descriptive” approach to developing a theory of change. By talking with people on the ground who execute programs day in and day out, you get a really great sense of the change you’re actually making and the goals implied by those changes. For us, this yielded a set of common outcomes like:

- Artists and arts organizations are able to raise and earn more money

- Artists and arts organizations save money and time

- Artists and arts organizations meet legal requirements for opportunities

- Leaders make better decisions on behalf of the cultural ecosystem

That’s all well and good, but there’s another way of going about a theory of change that is equally, if not more valuable. In this alternative approach, one starts with the goals: what change do we hope to make in the world, and what steps are necessary to achieve that change? I call this version the “aspirational” approach because it achieves great clarity on one’s goals, but may imply a different set of activities than the one your organization currently has. For the Fractured Atlas theory of change, we decided to try a combination of the descriptive and aspirational approaches. We started out by combining the major activities and near-term goals seen across the programs and laying them out at the beginning of the model. But then, separately, we took a look at our mission statement, which reads as follows:

Fractured Atlas empowers artists, arts organizations, and other cultural sector stakeholders by eliminating practical barriers to artistic expression, so as to foster a more agile and resilient cultural ecosystem.

If you were to diagram out that statement as a very simple theory of change, this is what it would look like:

You’ll notice that the outcomes from program activities in the set of bullet points I listed earlier are mostly just specific ways in which Fractured Atlas addresses “barriers to artistic expression.” So the good news is that, in our case, the descriptive and hypothetical approaches converge pretty neatly in the center. The Grand Theory

After many, many additional conversations, here is what our leadership team ended up with for our fully fleshed-out theory of change:

(Click to enlarge diagram)

As you can see, we concentrated most of our energies getting into more specifics about what a more “agile and resilient” cultural ecosystem would require. Where we landed was two broad concepts of diversification — of the voices in the sector and of the sources of support for cultural activity. The less dependent the cultural ecosystem is on any one or few of its parts, the more likely it is that it will be able to adapt and change with the times rather than get “stuck” in old ways of thinking and doing things. I should note that our conception of “diversity” and “diversification” is intentionally broad. In our sector, “diversity” has frequently come to represent a code word for race, with gender, sexual orientation and other markers of identity occasionally getting caught up in the definition as well. As a result, there is a strong gravitational pull towards standard demographic measures whenever we start trying to make these concepts concrete. But we’re using diversity here in its more literal, dictionary definition of variety or a range of different things. In practical terms, what this means is that we want to enable voices — artistic voices, that is — that wouldn’t otherwise be heard at all. Every time we do so, we add to the diversity of voices in the sector, regardless of that voice’s race, gender, geography, artistic style, or anything else. We don’t believe that every aspiring artist deserves a successful career, but we do believe that every aspiring artist deserves a fair shot at one. Adding Context In addition to the theory of change itself, we also spent some time specifying some contextual information that is often included with a logic model. These included the following elements:

- Inputs (i.e., the resources we have available to do our work)

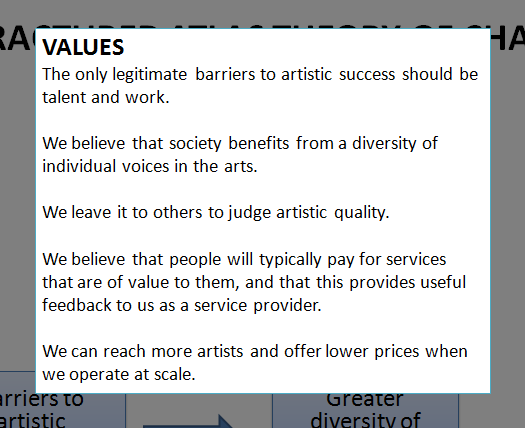

- Values (beliefs and faiths that influence how we accomplish our mission)

- Target Population (who our audience is)

- Assumptions of Need/Opportunity (assumptions about why the world benefits from an organization doing the work that we’re doing)

- Environmental Factors (trends and features of the landscape in which we operate that are relevant to our work)

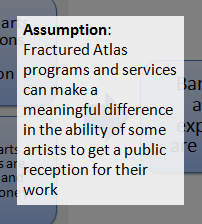

- Operational Assumptions (assumptions underlying the logical connections within the theory)

- Measures (indicators we can use to track progress on our outcomes)

Since this is already a long post, I won’t bore you with the full details of each one of these. But to give you a sense of what I mean, here is what we came up with for values:

And here’s an example of an assumption. This one relates to the outcome, “Barriers to artistic expression are reduced.” (We chose “reduced” as a more realistic framing of the ideals articulated in our mission statement, which states that we seek to “eliminate” practical barriers to artistic expression.) In order for that to be true, it needs to be the case that we’re helping at least some of our constituents get a leg up where that wouldn’t otherwise have been possible:

Let’s get back now to the challenge we articulated at the beginning: how do we define metrics for mission success? I want to draw your attention once again to the outcomes immediately prior to our ultimate impact of “a more agile and resilient cultural ecoystem”:

- Greater diversity of voices in the sector

- More diversified sources of support for cultural activity

We ended up choosing the following metrics to represent progress towards these ideas:

- # people who are able to get their completed work in front of a public audience

- total $ spent on the arts in the United States

- total # arts participants in the United States

- total philanthropic $ provided to bottom 98% of arts organizations by budget size

And those, ladies and gentlemen, are Fractured Atlas’s metrics for mission success. Making it Real It’s one thing to identify some things that could theoretically be measured, if we wanted to. An interesting exercise, for sure, but ultimately not very meaningful on its own. Better would be to identify the things that can be measured and then actually measure them. But for concepts as sweeping as the ones in the bullet-point list above, it could be hard to attribute any changes in the ecosystem to Fractured Atlas’s efforts. So why are we doing this, again? I’m convinced that the real value in defining mission metrics this way is in their potential to inform decisions. As part of the work of the Data-Driven D.O.G. Force, we’ve been exploring ways to analyze the decisions we make by predicting what might happen once we make them. So far, we’ve been limited in doing so because we had to define costs and benefits strictly in financial terms. What going through this process allows us to do is to make predictions about how some decision we make might or might not affect outcomes that we care about in the context of our mission. Now that we can do that, it’s possible to consider our decisions in truly holistic — yet still highly quantified — terms. I’ll be the first to admit that the use of mission metrics in decision-making models is by far the most experimental element of this project that I’ve been calling Fractured Atlas as a Learning Organization. I have high hopes for its potential, but we are only just beginning to try it out in practice. One question that’s very present in my mind right now is whether it was the right choice to focus on metrics that are at the very end of our theory of change — right before our ultimate impact. While this approach does a better job of capturing what we care about most, it creates more of a challenge for managers because the connection to everyday decisions is less clear. I fully expect that we’ll continue to refine these resources as we get more comfortable with them, and I promise to keep you updated as we do. In the meantime, I can testify that even the act of articulating our mission more concretely has sparked new conversations for us. We’re thinking more consciously about who we’re reaching with our programs now, and not just how many. We’re being more intentional about how all of our various activities fit together, and more thoughtful about what kinds of new challenges we take on. Even if we never end up measuring anything, those changes in behavior could pay dividends for years to come — for Fractured Atlas and the sector alike. We hope they will.

About Ian David Moss

Ian David Moss was the Senior Director of Information Strategy at Fractured Atlas, a nonprofit technology company that helps artists with the business aspects of their work. To learn more about Fractured Atlas, or to get involved, visit us here.