By Ian David Moss on August 9th, 2013

Collective Impact in the Arts

(This essay was originally written in my role as an outside consultant to the city of Calgary’s cultural plan. For this entry, I was asked to reflect on the possibility of developing a collective impact model for the arts in Calgary. You can read all of my contributions to that process here.)

Through its #yycArtsPlan process, Calgary has the opportunity to pursue what may be the first full-fledged collective impact model in the arts. Will it take the reins? Collective impact is a term coined by John Kania and Mark Kramer of the consulting firm FSG Social Impact Advisors in 2011. In a nutshell, the concept is this: the social sector is best positioned to accomplish real change through centralized, strategic, and coordinated action, rather than through decentralized and isolated interventions that can often work at cross purposes. This seemingly obvious insight is fleshed out in substantial detail in Kania and Kramer’s original collective impact article as well as many follow-up publications. Kania and Kramer outline five essential elements of any collective impact initiative, as follows:

Since the publication of the original article, collective impact mania has swept across the North American nonprofit sector. And yet, of the collective initiatives that have sprung up in response to this wave of interest, not one so far has specifically focused on the arts. This gap opens up an opportunity for Calgary to blaze a new trail yet again, but in doing so local leaders should be mindful of how collective impact differs from run-of-the-mill collaboration and consider the barriers that have kept the arts sector from fully embracing collective impact until now.

Collective Impact: A Giant Leap Forward Some of the requirements of the collective impact model may seem familiar to arts leaders at first glance. For example, it’s true that most large metropolitan regions in the United States and Canada benefit from a municipal or regional arts council, whether structured as a government agency or independent organization, and that these entities are the obvious candidates to provide the “backbone support” ingredient of the collective impact recipe. Likewise, cultural planning efforts (such as Calgary’s) aspire to create a shared vision around priorities and goals, much in the same way that collective impact requires a “common agenda.”

Nevertheless, even in the most collegial and infrastructure-rich arts communities, there are some key ways in which collective impact raises the bar for coordinated action. A major weakness of many cultural plans is that, once the document is written and the funded process for convening stakeholders has come to an end, it is difficult to sustain energy and motivation to implement the resulting recommendations. The three elements of collective impact not mentioned in the previous paragraph — shared measurement systems, mutually reinforcing activities, and continuous communication — are all about providing this missing link. We should not underestimate the extent to which a fully implemented collective impact model represents a radical departure from the status quo.

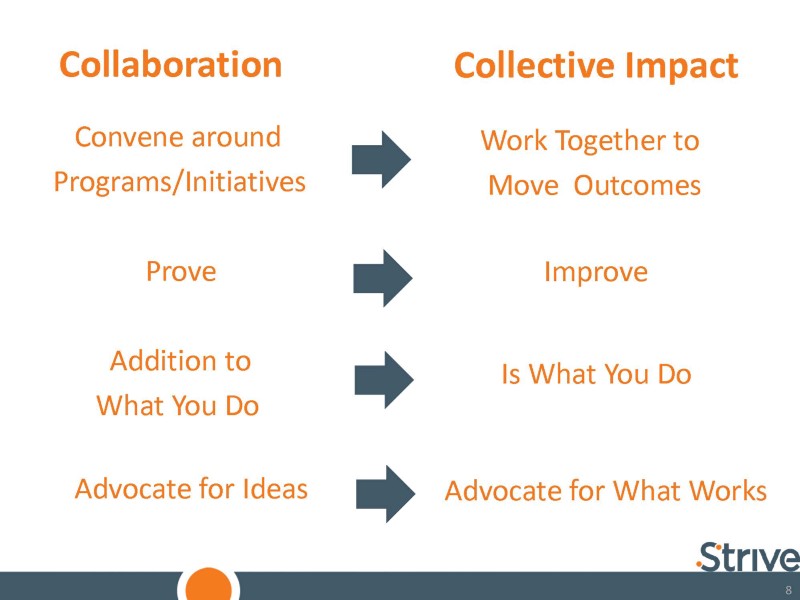

Collective impact is about more than just collaboration when it’s convenient and working together on isolated projects that happen to lend themselves to shared action. Collective impact requires the full commitment of all participants to a concrete set of goals, and alignment toward making those goals a reality through whatever means are most appropriate. It requires participants — including the so-called “backbone organization” leading the effort — to put the goals, not themselves, first. Jeff Edmondson, leader of perhaps the highest-profile collective impact model, Cincinnati’s Strive Network, puts it this way (emphasis mine):

…[C]ollaboration is often one more thing you do on top of everything else. People meet in coffee shops or church basements to figure out how to do a specific task together and in addition to their day job. Collective impact becomes part of what you do every day. It is not one more thing because it is truly about using data on a daily basis — in an organization and across community partners — to integrate practices that get results into your everyday contribution to the field.

Arts-Specific Challenges to the Collective Impact Model So why is it that the arts haven’t more rapidly embraced collective impact as a strategy? I can think of a number of possible reasons, ranging from the practical to the philosophical. On the practical side, the arts are an under-resourced field generally. And within the arts, unlike other areas of the nonprofit sector, philanthropic dollars tend to flow most readily to direct service delivery (i.e., local institutions and ensembles) rather than large infrastructure organizations (i.e., the arts equivalent of the American Cancer Society or UNICEF).

As a result, arts practitioners and funders alike often find themselves making do with shoestring budgets that don’t easily accommodate the level of staff attention needed by a collective impact initiative. Furthermore, the arts are not as well integrated with the rest of the nonprofit sector as other cause areas such as education, the environment, and social services, and thus have been slow to pick up on similar trends in the past. I do believe, however, that the practical barriers to collective impact can be overcome given sufficient motivation to do so.

I’m more interested in what I see as philosophical barriers: reasons why arts stakeholders may feel resistance to collective impact due to a perceived conflict with their values. I will go through each of these perceived conflicts and discuss why I feel that they need not be conflicts at all. Formulating the Problem Kania and Kramer define a common agenda as follows: “Collective impact requires all participants to have a shared vision for change, one that includes a common understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving it through agreed upon actions.” Note that vision under discussion here involves solving a problem.

This is one reason why the arts often don’t fit in easily with other nonprofit causes: what problem is being solved, exactly, by the Calgary Stampede or the EPCOR CENTRE? The arts are usually best presented as an opportunity rather than a problem: an opportunity for human beings to express themselves to the fullest and for others to witness, experience, and take part in that expression. Fortunately, the language of economics gives us a way of drawing an equivalence between problems and opportunities in the form of opportunity costs. By neglecting to take an opportunity available to us, we miss out on it, and that is a problem if it leads to a worse outcome. Thus, while the problem-solving language of collective impact may feel somewhat alien to arts stakeholders, conceptually it should not stand in the way of forming a shared agenda for the arts.

Measuring the Unmeasurable Collective impact’s emphasis on shared measurement systems is not just about measuring progress towards a goal — it’s about holding participants accountable for moving a vision forward into reality. Otherwise, vague conceptualizations of the road ahead leave open the potential for multiple and self-serving interpretations of how far we have to go, or if we’re even still on the right path. The arts, however, have a particularly fraught relationship with measurement and data. One explanation lies in the resource challenges described above — measuring things takes time, money, expertise, and effort, and arts organizations are often stretched for all four.

But I believe there’s another factor at play as well, which is that many in the arts simply bristle at the idea of their work being reduced to a number or a statistic. They have seen quantitative data being misused in other contexts, and are afraid the same thing could happen to them. And besides, how can you express the pure joy of creation in a bar graph? These concerns are understandable. But a truism of measurement is that if it matters at all, it can be measured.

That doesn’t mean that measurement is always easy — but the tools we have available to us for research are remarkably flexible and adaptable to almost any situation. It’s applying them in a scientifically valid manner that is the challenge. So-called “intangibles” are very much measurable, and people have been measuring them for centuries. If the arts really are healing souls and changing lives, that is going to show up in the data if the right data is being collected. It’s important to note that, in order for a collective impact model for the arts to work in Calgary, the #yycArtsPlan process will need to get much more specific about defining concrete data points to associate with the values articulated in the cultural plan.

Right now, the plan articulates five goals, some of which readily lend themselves to quantification (“every Calgarian under 18 has the best possible opportunity for arts participation and education”), and some of which don’t (“create a new postcard of Calgary!”). Regardless, it is agreement on these common goals and ongoing tracking of the associated measures that will create the environment of accountability needed to see the vision through. Diversity vs. the Borg Critics of collective impact have enjoyed comparing the model to the Borg on Star Trek: The Next Generation: “Resistance is futile.”

The reference conjures up an image of faceless robot-like entities that have no individuality, but are instead controlled by some unseen “hive mind.” Such a nightmare vision seems antithetical to the values of the arts, which celebrate diversity, variety, and above all, individual expression. Wouldn’t a collective impact model, with its shared goals and need for structure, interfere with the essence of what the arts are all about? Actually, I don’t think it needs to — if that model is implemented well. Collective impact means that everyone is working towards the same goals, but contrary to a common misconception, it does not mean that everyone is doing the same things. Just as a homemade meal tastes no less delicious if one cook chops the vegetables while another marinates the meat, collective impact implies a division of labor among participants that nevertheless are all committed to a common goal.

Thus, it’s not a problem for one organization to focus on presenting classics of the Western canon while another creates opportunities for immigrants while yet another celebrates the creative achievements of our brightest four-year-old minds — as long as they all understand precisely how their work fits in to the broader puzzle of a creative Calgary and can make decisions accordingly. Looking Ahead Much work still needs to be done before Calgary will truly be ready to take on the first arts collective impact effort. And yet Calgary has already made great strides in building a supportive environment for this sort of collective action.

In addition to firming up the will and buy-in among local participants for moving forward, Calgary arts leaders will need to translate the #yycArtsPlan’s goals into clear, quantifiable targets that the entire community can rally behind. They will need to set up structures for regular communications among relevant parties and shared data and knowledge networks that directly relate to the vision’s targets. And they will need to define a set of mutually reinforcing activities that the existing arts community can map on to, pinpoint what gaps lie between the current reality and the desired outcomes, and formulate specific strategies to close those gaps that take maximal advantage of the community’s assets. It’s going to be an ambitious ride, and I can’t wait to see how it all turns out.

About Ian David Moss

Ian David Moss was the Senior Director of Information Strategy at Fractured Atlas, a nonprofit technology company that helps artists with the business aspects of their work. To learn more about Fractured Atlas, or to get involved, visit us here.